Basil Minns: “Father of the Moriah Harbour Cay National Park”

By: Elijah Sands, Leah Carr

Born in George Town in 1929, Basil Minns is a fourth-generation Exumian who’s dedicated much of his life to protecting the rich environment of the island he loves and has spent most of his years on. What he refers to as “the actual jewel of The Bahamas,” Exuma is home to an abundance of marine and terrestrial wildlife- wildlife Basil grew up watching and interacting with. His up close and personal experiences with nature sparked an appreciation for its beauty and significance in him at a young age. This recognition of nature’s significance is what has driven Basil’s lifelong work- work for which The Bahamas National Trust (BNT) proudly acknowledges him along with his wife, Jane Minns, as Conservation Legends. Basil also had the honour of receiving the 1999 Cacique Award for “Nature Tourism” for his conservation efforts.

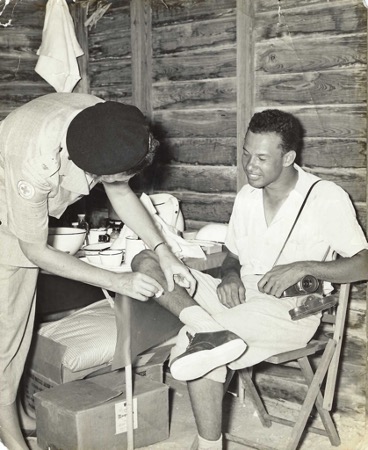

Black and white photos of a young Basil Minns.

We had the privilege of sitting down with Basil Minns and listening to him share some of his stories. He talked about tourism in The Bahamas in the early days, witnessing the decline of biodiversity with his own eyes, and also the growth of the conservation movement in The Bahamas over time.

There are many incredible people behind the work of the BNT and the national parks we strive to protect. From those who led groundbreaking research to save at-risk species to those who championed efforts to protect areas of significant natural importance; Basil Minns is certainly one of the people on the top of our list whose story can’t go without sharing.

Among his many endeavours, one of Basil’s greatest legacies is that of being the “father” of the Moriah Harbour Cay National Park (MHCNP): a national park in Great Exuma that encompasses over 27,000 acres of pristine beaches, sand dunes, mangrove creeks, seagrass beds, blue holes, and coral reefs. The marine environments protected in this park are a vital part of the Exuma chain of islands. After decades of petitioning by the local community, the area was officially declared a national park by the Bahamian government in 2002. It wasn’t easy getting this park created, and most of the legwork for this achievement was led by Basil and Jane Minns.

Coral Reefs in the Moriah Harbour Cay National Park

As longtime members of the BNT, Basil and Jane were already huge advocates for the environment and Bahamian national parks way before the creation of the MHCNP.

“I remember going to California and visiting other parks around the world, and on our way back, our flight was right over the Exuma Cays. I said to Jane, ‘Why do we go away? We got all the beauty we need right here,’” Basil recalled.

“I was introduced to an astronaut one time who’d been up circling the earth and came here to Exuma. He said the Exuma Cays reminded him of an emerald necklace going around the earth. Moriah Harbour Cay is the closest thing we have in this area to the Exuma Cays.

“It’s okay having a park in the cays,” he said, speaking of the prestigious Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park (ECLSP) that was created in 1958, “but of course you needed a boat to get there, and a lot of people weren’t capable of doing that in those days because they didn’t have the facilities. We started thinking we needed something here in mainland Exuma.”

Basil knew Moriah Harbour Cay and its surrounding areas would be the perfect area for a national park. It had an abundance of wildlife, important habitats, and offered people numerous ways to connect with and enjoy the wonders of nature. Additionally, it was the closest ‘rival’ to the Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park in beauty.

The Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park, the first national park created in The Bahamas

But bestowing Moriah Harbour Cay with its own laurels as a national park like the ECLSP was not easy or quick. “It was a struggle from the very beginning,” Basil said. “We wrote letters, talked about it to people and local government, but we couldn’t get anything established.”

It was circa 1998 when a group of developers visited Exuma with their sights set on Moriah Harbour Cay. Tipped off by a contact he had from his years working with the Ministry of Tourism, Basil managed to get an audience with the business group. Of course, their development plans had little to no regard for the natural beauty that already existed on the cay, and their development would be devastating to the natural environment. So Basil set them straight…

“I said, ‘Now, wait a second– it’s already a beautiful area and everything you’re talking about would destroy it. I think you should leave it as it is.’ Well, he had his good argument about what the developer/development would do for the island and whatnot,” Basil said with a smile. “So that prompted me to go to battle for Moriah Harbour Cay.”

Moriah Harbour Cay, the namesake of the national park.

The fight to declare Moriah Harbour Cay a national park began. Basil and others held public meetings, started a government petition, wrote numerous letters to environmental and governmental agencies, and created a proposal to be carried forward by the BNT. It was a process that endured for years, with Basil and Jane leading the way. Support for the cause grew and the fight to save Moriah Harbor Cay built more traction as time went on.

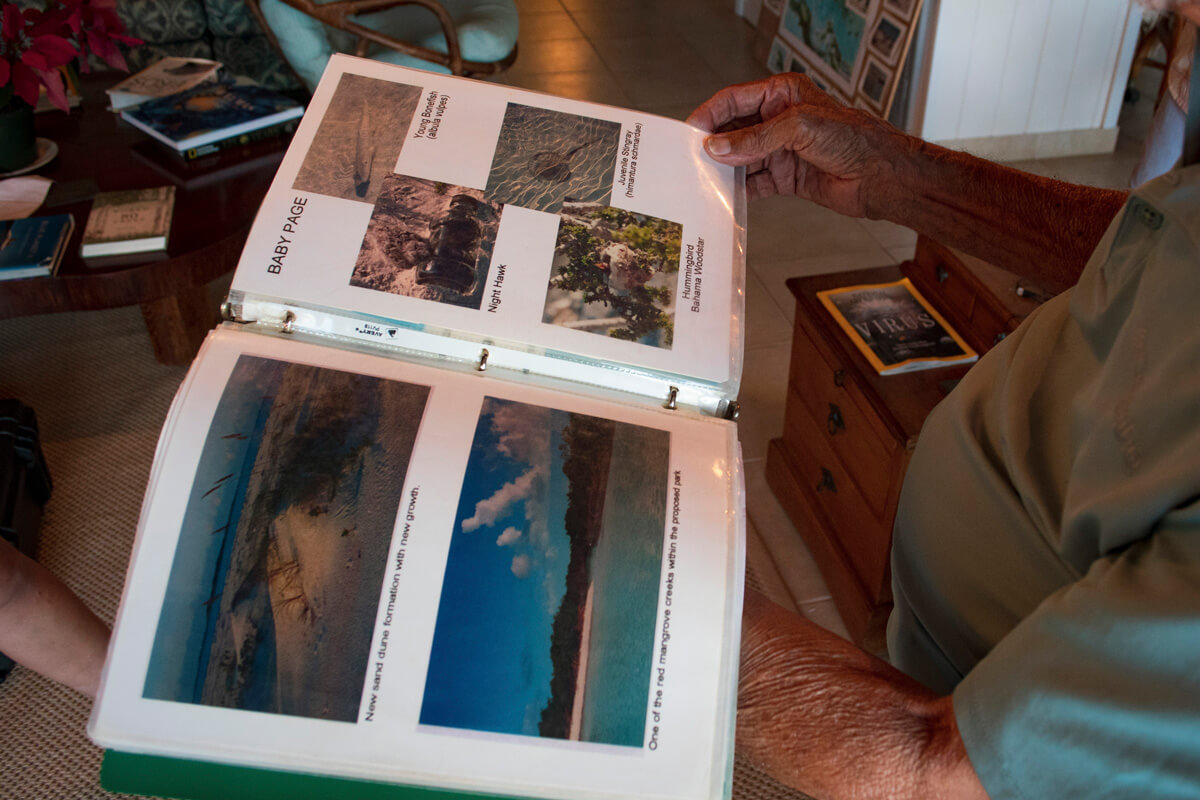

The proposal that was submitted to the BNT was one of a kind. It was a comprehensive booklet, containing many photos, scientific reports, and other information showcasing the importance of the area and building a case for a national park to be created. It was the first and only time community members submitted a proposal to the BNT to be put before the government.

Basil, being a prolific photographer, had many photos showing the beauty of Moriah Harbour Cay and the surrounding area. He used many of these photographs in the original proposal that was submitted to The BNT.

“One of the people that actually clinched the deal was Hubert Ingraham, who was Prime Minister at the time, came down here to the Family Island Regatta,” Basil recalled. “I told his aide I’d like to talk to him about what we were hoping to do. He said, ‘Come out and see me at breakfast tomorrow. That’s the only time I have free cause I’m leaving on the plane at 10 am.’ So I talked to him about it, and believe it or not – that was April 2002, and PM Ingraham made an announcement in May 2002 that Moriah Harbour Cay would be added to the parks system of The Bahamas, which was a great feather in our cap.”

Although the Prime Minister declared Moriah Harbour Cay a national park in 2002, the fight for Basil Minns, the BNT, and its supporters was not over yet. The government had only accepted one-third of the proposed area as a protected area. The areas that were excluded from the consensus included Pigeon Cay and the eastern end of Stocking Island. These two areas were game reserves for hunting birds and also areas locals used to collect palm leaves for straw work.

Pigeon Cay alone was an area of great value that was worth continuing the fight for. It was a very important site for nesting birds.

“I remember going to Pigeon Cay as a kid with family and friends who were hunting pigeons. When that first gun went off– the birds that flew over the top of the island were like a blanket. There were so many of them, it literally blanked out the sky. They went up a couple hundred feet in the air and circled the island, and there were just thousands of them.”

Pigeon Cay in the Moriah Harbour Cay National Park is home to endangered Rock Iguanas and nesting seabirds.

Sadly, those numbers of birds don’t exist on Pigeon Cay anymore. Hunting and the poaching of eggs, along with human disturbance and other factors, significantly reduced the number of birds now present on the cay.

Today there are also endangered Rock Iguanas on Pigeon cay. These iguanas have a special story of their own. They were stolen off of White Bay Cay, a cay further south in the Exuma chain, and smuggled to Europe by two foreign visitors. Luckily, the two women were apprehended in the airport in London, and the surviving iguanas were brought back to The Bahamas.

To avoid transmission of any virus or disease the iguanas may have picked up while being smuggled, they weren’t released back on their original cay, to avoid endangering the other iguanas. Therefore, research was conducted and discovered Pigeon Cay was a suitable site for them, and they were put on Pigeon Cay.

Thankfully, after years of more petitioning and more effort, including more community consultation, Pigeon Cay and other areas included in the original proposal were designated as part of the Moriah Harbour Cay National Park in 2015.

Basil credits his wife for much of this accomplishment in getting the MHCNP established. “I had a lot of ideas, but Jane did the grunt work of the letter writing and phone calls and all the rest of it. All I had to do was mention anything, and she would research it. She loved to research.

“She was in love with the area because we spent a lot of time there. If weather permitted we’d have a picnic on Moriah Harbour Cay on our birthdays- just the two of us. We’ve seen a lot in the park over the years: huge stingrays, eagle rays, barracuda, lemon sharks. She wrote letters to the papers explaining what the area meant- what we were looking to protect.”

Much has changed in the Moriah Harbour Cay National Park over the decades, but one thing remains the same: its natural beauty and resources are still worthy of protection.

The mangrove creeks on Moriah Harbour Cay are important areas for juvenile lemon sharks, sea turtles, and other marine life.

Basil and other locals recall much greater numbers of wildlife in the area in the past. Increased visitation and unsustainable practices threaten the biodiversity found within the park boundaries.

Marine-protected areas like Moriah Harbour Cay National Park are one of the best ways we can protect natural resources, which are not only vital components of their ecosystems but significant parts of Bahamian culture as well.

National park sign in Moriah Harbour Cay National Park.

In 2018, The Bahamas committed to protecting 20% of our nearshore and coastal marine environments by 2020 as part of the Caribbean Challenge Initiative. To date, only a little over 10% of these environments are protected. Many, including Basil, are waiting to see these new protected areas officially declared.

As chairman of the Tourism and Environmental Committee in Exuma, Basil was a part of the group that created recommendations for all government-owned property on the mainland that should be protected; this included parks, beach reserves, and historic sites spanning from Sandy Cay (White Bay Cay) to Barraterre.

But The Bahamas needs more than just additional protected areas. We need people interested and working to protect these areas.

“That’s the thing I’m worried about,” Basil said. “Getting enough people involved. We need to educate the general public, go into schools, and work to get more and more people interested in conservation. The BNT is doing a good job, but we need other organizations and more people to get involved as well.

“I’m proud to be recognized as a Conservation Legend and I’m proud of my legacy. What I’m disappointed in is not having enough disciples. We need more people taking up the gauntlet and doing some of the things I did. Because there’s still a lot of work to be done, a lot of areas that need to be protected, and a lot of education that needs to happen.

“We need the people of Exuma to realize we have a gem in The Bahamas. It’s a beautiful island. It’s got a lot that should be protected and preserved for future generations. And we have to let people know that it doesn’t belong to us. It’s a trust for future generations. And we, the generation that’s here now, need to do our part to make sure we keep it in the best shape we can. What’s my great-great-grandson going to save if we don’t protect something today and just let it all go to waste?”

Basil admiring his BNT Conservation Legend trophy.

Basil says, “he still has it.” As he shows off a panoramic photo recently taken on his smartphone.

To honour Basil’s legacy, the BNT with support from its partners dedicated the education gazebo on Stocking Island to him. Designating it “Basil’s Classroom,” this outdoor space will be used to educate the youth of Exuma about their environment, and also as a place to inspire and introduce young people to conservation and their national parks.

Basil’s classroom on Stocking Island.

During the dedication ceremony, we also honoured Basil’s late wife, Jane Minns, as a Conservation Legend for all her efforts alongside Basil to create the Moriah Harbour Cay National Park. He was overjoyed for this and showed that he still has the fiery passion he exhibited during his years of fighting for this area to be protected.

Basil is proud of his legacy. The hard work paid off with the creation and expansion of the Moriah Harbor Cay National Park. He’s extremely grateful to have had his wife, Jane, by his side, and also his children who he said have followed in his footsteps as being stewards of the environment.

The BNT, through funding from the Global Environment Facility, plans to improve the management of the Moriah Harbor Cay National Park by 2022. These advancements will include constructing a headquarters on Great Exuma, acquiring a patrol vessel, and hiring a park warden.

To stay involved with the work of the BNT, follow us on social media and become a member today!

After 61 years of leading conservation in The Bahamas, we launched a new brand to retell our story. There’s never been a better time to join our mission and be a part of the community working to protect The Bahamas for future generations.

Editor’s Notes: For most of my talk with Basil, I wasn’t interviewing him; I sat there taking in one of the most relatable conversations I ever had. Basil, as a photographer, naturalist, and advocate for Bahamian national parks, said so many things that I share the same concern and views for.

It joyed me to know that I was also capturing it on film. I’ll now be able to take Basil’s story, his history, and knowledge, and use it to inspire others to support conservation and national parks.